In a digital world shaped by algorithms and endless scroll, Detroit’s independent bookstores feel almost radical. They ask people to slow down. To browse, linger, talk, and think. To feel something other than the buzz of the next text. And somehow, in a moment where convenience seems to win every time, these spaces are not fading — they’re holding their own in communities where people treasure them.

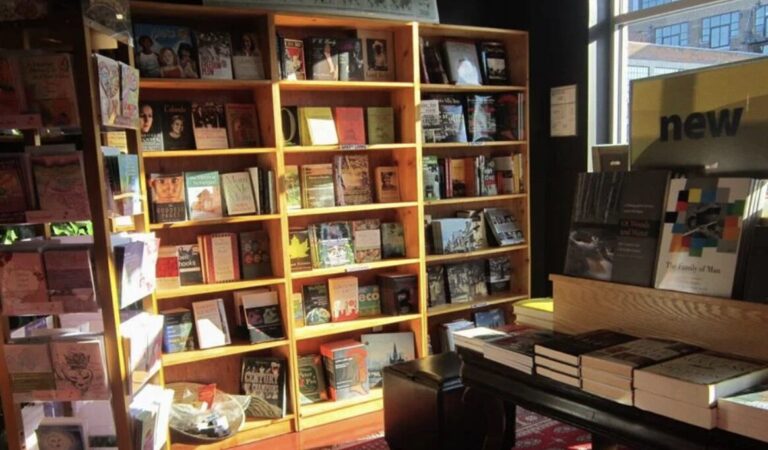

At Source Booksellers in Midtown, founder Janet Webster Jones puts it plainly: “Independent bookstores sit inside the community. Our value is in our customer service and our curation.” She references a Harvard study that found three traits uniting successful indies: community, collaboration, and curation — a perfect summary of Detroit’s literary landscape.

JANET WEBSTER JONES

Her shelves reflect something our digital culture keeps forgetting: “Pixels don’t fit into the thoughtful part of our brain,” she says. “Our brains learned print long before they learned screens.”

The customers who step into Source feel that. They’re met with a store shaped not by algorithms, but by intention — memoirs, biographies, books by Detroit legends, deep nonfiction, climate titles, women’s histories. Jones says, “We curate based on what aligns with our mission and the community’s needs. Big-box stores can’t do that.”

Across the city, similar stories unfold — different shops, but the same belief: books remain one of the most important commodities we have.

“Detroit has so many stories that never made it into national history,” says Jelani Stowers of Pages Bookshop in Grandmont Rosedale. “A bookstore in the city becomes the place where those stories can be shared, archived, honored.”

PAGES BOOKSHOP

At 27th Letter Books, co-owner Andrew Pineda talks about the importance of connection. “Books become glimpses into another person’s existence,” he says. “In our store, we view them as windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors. They let readers see the world in a new or different light, or see themselves reflected in the art. Online shopping doesn’t allow for that kind of connection.”

This is also echoed at Next Chapter Books on East Warren, where owners Sarah and Jay Williams walk four blocks from their home to their shop each morning, greeting neighbors along the way. “We aren’t just a business asking for a neighborhood’s support,” Sarah says. “We invest our money back into this community. That matters.”

27TH LETTER BOOKS

She’s honest about the industry’s biggest challenge: “The convenience of online shopping has been the indie bookstore’s challenge for 20 years. Amazon is a heartless monopoly that has taught people to devalue books, authors, and the skillset of booksellers.”

Her solution — and her store’s ethos — is the opposite of convenience: it’s connection. “Algorithms don’t build community. Intentionality does.”

At Vault of Midnight, Detroit’s beloved comics-and-graphic-novel hub, owner Curtis Sullivan describes their role with refreshing simplicity: “Anybody can sell stuff. Selling stuff face to face is totally different. We’re a place. You remember your visit.”

Their customers span generations; parents who once visited as kids now bring their own children. “People want to be with people,” he says. “Being a real part of someone’s day has value again.”

SARAH AND JAY WILLIAMS NEXT CHAPTER BOOKS

And Pineda points out that the stakes are higher than just commerce. “One of the biggest challenges isn’t Amazon — it’s a culture that views literature and the arts as inessential. Earlier this year, huge NEA funding cuts sent a message that the arts don’t matter. So we see our store as a place where people participate in the cultural dialogue. That’s part of our job.”

Those threads — value, presence, community — weave through everything these owners say.

In pop-ups throughout Detroit, Detroit Book City adds another essential dimension. Founder Janeice Haynes specializes in African American literature and describes the physical book as “a priceless commodity… something you pass from generation to generation.”

VAULT OF MIDNIGHT

For her, the bookstore is both cultural archive and cultural reawakening. “Historically, many African Americans did not have access to books. That’s still a challenge. So we host book fairs, pop-ups, author events — we entice people back into reading.”

Janeice says people are interested in books that focus on self-esteem, mental health, Black history, memoirs, children’s literature: “Books that shape how people see themselves.”

She says the biggest opportunity today is simple: “Have bookstores in the neighborhoods. More access means more reading. The more we connect to books, the better the world will be.”

The challenges these booksellers face — attention scarcity, online undercutting, limited square footage, competition from screens — are real. But their solutions are straightforward and deeply Detroit:

- be present

• be human

• be intentional

• serve the community

• curate with care

Jones calls it “a privilege to serve the literary life of the community,” a phrase that feels like the thesis of Detroit’s indie bookstore presence. She defines literary life not as literacy alone, but as an everyday practice: “Listening, speaking, writing, reading — that belongs to everyone.”

DETROIT BOOK CITY

A bookstore, in her opinion, is a civic space as much as a retail one.

At Pages, Detroit and Michigan histories remain top sellers, along with cookbooks and poetry. At Next Chapter, readers reach for books on social justice, mutual aid, political science, and Palestinian literature — “people seeking truth,” Sarah says. At Detroit Book City, readers want healing, confidence, representation, and the stories of Black Americans whose lives shaped the nation.

At 27th Letter, Pineda says their curation centers a simple but profound aim: “When the world feels isolating, it becomes even more important to read and be in community with each other.” He cites a James Baldwin line as a guiding principle: “The role of the artist is exactly the same as the role of the lover. If I love you, I have to make you conscious of the things you don’t see.” That, he says, is what they hope their bookshelves can do.

But beyond the trends and challenges lies something more elemental: bookstores as third spaces — not bars, not cafes, not workplaces, but sanctuaries for curiosity.

“People came out of the pandemic craving community,” Sarah says. “They still are.”

Sullivan sees it every time they host a game night or art show: “It’s not just a store. It’s part of the community.”

And Pineda believes the future depends on leaning deeper into that identity: “Bookstores have to think about what they’re doing beyond retail, because shopping online is too easy. The opportunity is to lean into what makes your community unique.”

Jelani says, “A bookshop is one of the few places designed to push you out of your comfort zone — to help you discover something you didn’t know you needed. The digital world keeps you comfortable. A bookstore expands you.”

And Jones, with her decades of perspective, returns to the foundational truth: “Service is the key. When we serve the needs of the community — what they want to know, how they want to grow — we are doing what bookstores have always done. We are keeping the literary arts visible.”

As always, be sure to subscribe to our newsletter for regular updates on all things Detroit.