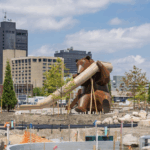

When Ralph C. Wilson Jr. Centennial Park opens this October, the centerpiece won’t be a monument or a sculpture—it will be something much more alive. Nearly 40,000 native perennials, grasses, shrubs, and trees will transform the formerly flat, industrial site on Detroit’s West Riverfront into a dynamic ecological experience.

At the heart of it is the Water Garden, a new kind of community space that blends nature, biodiversity, and access to one of the city’s greatest natural resources – the Detroit River.

“One of the things people have always told us is they want more natural areas along the river and more access to the river,” says Rachel Frierson, Chief Operating Officer at the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy. “The Water Garden is our response to that.”

The Water Garden will bring river water into the park in a controlled, ecologically sensitive way, creating a safe, close-up interaction with the water, surrounded by a living tapestry of regional plants.

Matthew Micael, a landscape architect with Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates (MVVA), the firm leading the park’s planting and landscape design echoes Frierson’s statement. “We designed this specifically to give people a direct connection with the river. It’s more than aesthetics or programming—it’s about giving people a chance to engage with water in an immersive, meaningful way.”

MVVA began the project with a bold vision: restore native ecological patterns to a site shaped by a century of industrial use. The firm’s designers started by studying the broader regional ecology and asking what plants historically thrived here, even if they’d been pushed out by pavement and infrastructure. Then came the practical considerations – what would thrive in Detroit’s climate, require minimal maintenance, and support long-term resilience?

The resulting plant palette includes 35 species of trees, 13 species of shrubs, and 33 different grasses and perennials. “The numbers are big,” says Micael. “We’re planting 967 trees, 2,413 shrubs, and 38,546 perennials and grasses. And many of these were custom grown just for this park.”

Seasonal diversity was another major consideration. Cherry blossoms in the spring, vivid fall color from oaks and honey locusts, and weeping evergreens in winter all ensure that the park will feel alive year-round. “We want this to be a place people return to over and over again, because it’s always changing,” says Micael.

Topography also plays a key role. Prior to redevelopment, the site was flat and open. MVVA introduced carefully sculpted landforms to create microclimates for plants and wildlife, buffer the play areas, and add spatial drama to the gardens. These hills and curves make the gardens feel immersive.

For the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy, which oversees the park’s development and operations, the gardens will offer residents and visitors an opportunity to engage with the Detroit River like never before.

“It’s a place where people can experience nature in an immersive way, right in the middle an urban environment.”

The design brings in some of the clearest water from the Detroit River, filtered through native plantings that help remove pollutants and demonstrate ecological principles in real time.

The Conservancy has partnered with the Huron-Clinton Metroparks on programming around water testing, environmental science, and habitat observation. It’s an outdoor classroom for field trips and public programs—but also a place for solitude, reflection, and delight.

“We’re so lucky to have this river,” says Frierson. “It’s one of the cleanest in the Great Lakes system, and yet people still don’t think of it this way. We want the Water Garden to change that perception—to help people see the clarity, the movement, the life.”

The planting strategy reflects years of public input. The Conservancy has hosted seven community meetings – with more to come – engaging Detroiters in every aspect of the park’s design. Twenty residents even traveled with the team to parks in New York and Chicago to see what might work best for Detroit.

“They wanted shade. They wanted native plantings. They didn’t want a big field of turf,” says Frierson. “We heard that loud and clear. And now we’re planting over 900 trees.”

That same attention to accessibility extends to maintenance. Pathways and access points were designed not only for visitors, but also for crews to easily care for the landscape without damaging sensitive areas. Plants were selected to require little or no pesticides or fertilizers.

As the final phases of construction and planting unfold this summer, Micael is already looking ahead to how the landscape will evolve.

“From day one it will be beautiful,” he says. “But over the years, it will change. We’ll see which species thrive, how the bird population shifts, what kinds of aquatic life start to live here. It’s a living system. That’s the most exciting part.”

For Frierson and the Conservancy, the gardens are part of a much larger transformation. With the East Riverfront now fully developed and two additional miles of the West Riverfront soon to open, Detroit is redefining itself through green space, equity, and environmental stewardship.

“This is the first time since Detroit’s post-colonial founding that this site has been transformed for something other than heavy industry,” Frierson notes. “We’re returning it to the people—and to the river. That’s a powerful moment.”

As always, be sure to subscribe to our newsletter for regular updates on all things Detroit.