Detroit, Michigan. Martin Luther King Jr. addresses a packed audience inside Cobo Arena as part of a freedom rally organized by the Baptist minister and civil rights activist, C.L. Franklin. His 21 year-old daughter, Aretha, is in NYC. Up to this time, she has released five studio albums with Columbia Records.

Although absent from the March, her spirit is with the civil rights movement—as it will be for the rest of her life. Her dedication in word, thought, and financial contribution are well documented—from her lifelong friendship to with Rev. Jesse Jackson to her offering to post bail for Angela Davis.

Much has been written on Aretha. And much glossed over. Her life was messy. At ten, her mother died. By age 15, she had two children of her own. Her father, the man with the “Million dollar voice,” had his own troubles. But, let’s not forget this is the Queen of Soul: the first woman inducted into the Rock n’ Roll Hall of Fame, winner of 18 Grammy awards, etc. A woman who has been through the worst of it and thrived.

Her career carried her to NY and LA, yet she never cut ties with Detroit.

In a moment when Detroit is going through great transformation and words like “renaissance” and “rebirth” seem to be on the tip of everyone’s tongue, Aretha’s life serves as a thread connecting the past and a reminder that Detroit never stopped being powerful—being important. That life is sometimes difficult and that this city’s hard times, like Aretha’s, are also the source of its power.

This is where we begin a conversation with her friend and longtime Detroiter, Larry Mongo.

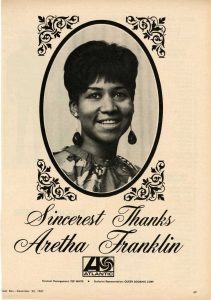

Aretha Franklin. Courtesy Detroit Historical Society

Detroitisit: What are your favorite Aretha Franklin songs?

Larry Mongo: Ain’t No Way. Bridge Over Troubled Water. Then all the rest of them.

DII: Why those two?

LM: For some reason, they touch me in some way. The first one, Ain’t No Way is very, very personal. When I was very young, and my wife and I were first married, she loved me, and she knew I loved her, but I had a hard way of showing love. What she wanted from me, that song told the story. I knew that’s what her heart was saying to me.

Bridge Over Troubled Water tells a lot about my inner-feelings, the real me—at that time. Simon and Garfunkel made it, but Aretha put a spin to it that touched me. I could relate to it.

The rest of the songs, like most songs, were just a hustle. Like life, it was a hustle.

DII: You knew her?

LM: I knew Aretha well—very, very well. Mayor Young—it was either my 35th or 40th birthday, he gave me a party at the DIA for 100 people and Aretha Franklin sang for my birthday party. I had known her for years. She hung out at my Uncle Red’s shoe shine place, she brought her shoes there.

She was my favorite. Mayor Young knew that. Aretha knew that. She liked hustlin’ type guys. She didn’t like square guys at all. She liked her sharp, flashy, men. I think I fit that, even though there was no type of relationship. Street style men that dressed well. That handled themselves well. That’s what she was drawn to, the streets.

A lot of her early songs that were so emotional. The street people, we have private stories behind those songs. She was a very private person, but we understood those songs more than the public did. Songs like Chain of Fools—that was one of my favorites—we knew who she was singing to. She was in pain with a lot of those songs. And it was a love pain.

DII: Did you stay in touch?

LM: She used to come to this club before it was Café d’Mongo, when it was Café Joseph. She would come, hang out. Not for long because people knew her. All the hustlers were here. She liked that flame.

DII: What are some things about Aretha that Detroiters know that the rest of the world doesn’t know?

LM: Her black pride. With all her fame, she knew that, by living here—by staying here—in Southeast Michigan, she was keeping Detroit on the map. She wouldn’t abandon Detroit. She would not abandon the people who made her. She tried to go to California for a minute. None of that worked. She had pride. Remember, her father was in the civil rights struggle. When I say having black pride, I don’t mean hatIing white people. No. It was black pride—and the pride that “black people made me and white people helped launch me to super stardom.” It was the love that black people had for her music. Her music was black gospel music in the beginning. And she never abandoned it. She never, ever abandoned us.