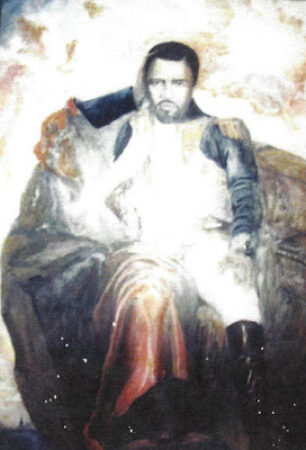

Napoleon Bonaparte may not be the first person you associate with Motown legend, Berry Gordy, but maybe he should be.

In the year Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going” on was released, Motown’s leader, Berry Gordy, unveiled a portrait of himself dressed as the French military leader and emperor. And the Smithsonian is still looking for it.

Commissioned by Gordy’s sister, Anna Gordy Gaye, as a gift to her brother, the artist Devon Cunningham, went through three versions before she finally chose her favorite, a portrait of Motown’s founder dressed as Napoleon.

In the first painting, Cunningham dressed Gordy in a suit.

Anna rejected it.

In the second, he portrayed Gordy in a classic stance with Detroit in the background.

Again, Anna rejected it. This time, she invited Cunningham to Motown studios, to see her brother in action.

During his visit, Cunningham witnessed an argument between Gordy and Anna’s husband, Motown recording artist Marvin Gaye. Gordy rolled up his sleeves. When the two emerged from the recording studio, Cunningham recalls Marvin’s words to his wife, “Your brother won again.”

Cunningham returned to the studio and painted Gordy in shadows, with his sleeves rolled up.

This third painting was rejected.

UNVEILING

DEVON CUNNINGHAM PAINTED BERRY GORDY AS NAPOLEON

For his fourth and final attempt, Cunningham presented a painting of Gordy dressed as Napoleon. Anna loved it.

As did her brother, who unveiled the portrait on April 25, 1971, at the Sterling Ball, a Motown event that raised money for scholarships for inner city children. The gala was held in Gordy’s Boston Edison mansion, where the portrait remained before Gordy relocated to California, taking it with him.

It was a big deal night.

Among the famous personalities in attendance was a young Michael Jackson who is rumored to have been in awe of the painting. Some speculate that it was the inspiration behind the pop idol’s Napoleon-esque military outfits.

MISSING PAINTING

By the time the Smithsonian tracked down Cunningham’s daughter to find his long-gone painting, much had been lost to history. What happened to the art, but also why was it painted?

Many assumed Gordy had commissioned the painting himself, out of an inflated ego. People made comparisons based on height—Napoleon was famously short and, well, Gordy wasn’t the tallest.

Some, like Larry Mongo, of Cafe d’Mongo, speculate that Gordy destroyed the painting when he outgrew the image. After all, one’s views—of themselves and of the world—change with age.

Others seem to simply be confused by the situation. Indeed, the distilled image of Berry Gordy dressed as a French general, without context, is absurd. Especially if one imagines him dressing in full regalia for the occasion—which he was not.

RECOVERY

In the decades since Anna Gordy commissioned Cunningham to create a portrait of her brother, he has enjoyed a successful art career.

Since contacting him seven years ago, the Smithsonian has acquired multiple pieces of his work for their permanent collection. Gordy’s portrait has been added to the museum’s catalog, marked by a faded, flash stained photo of the portrait, captured as it once hung in Gordy’s home.

The original has been lost to history—along with something far more valuable: the feeling that surrounded it.

There’s no doubt Gordy was a force. The man changed the recording industry in a profound way. Years after the incident that would inadvertently inspire the famous portrait, Marvin Gaye called Gordy a “grand warrior.”

POSTERITY

The details of this story come from a phone call with Cunningham himself, coordinated by his longtime friend and collector, Larry Mongo.

When asked what the portrait meant to him, what it meant to see Berry Gordy dressed as such a grand character, Mongo’s response was immediate:

“That portrait gave all of us black pride. It was a great metaphor. It was created during a great period of black upheaval.

Berry Gordy was Napoleon to us. He conquered the music business.

There was power in seeing the Supremes and the Temptations on the Ed Sullivan show. Those were the black people we saw in the streets. They didn’t need any alteration—which gave us unbelievable pride that we could be black, and white America accepted us.”