The social media thank you notes to Detroit began almost as soon as Michigan was declared blue in the 2020 presidential election. One twitter user, Sam Richardson tweeted on November 4th, “Let it never be forgotten that Detroit showed up when America needed it. The blackest city in America. Put some respect on its name and its people.”

When Detroit’s votes were counted, the polarization of the city was clear. 233,908 votes were cast for Biden, equating to 93.5%, 12,654 were cast for President Donald Trump, totaling 5%, and 3576 were cast third party, making up less than 2% of voters.

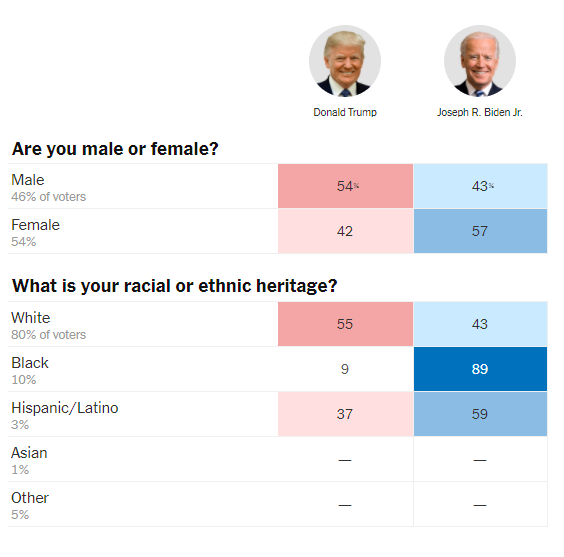

It is clear that Detroit, with its 4.5% of Michigan voters and this stark polarization, helped swing the election toward President-elect, Joe Biden. According to the New York Times exit polls, 89% of Black Michiganders voted for Biden. This accentuates the pull Detroit had on this election as a city made up of 78.6% of Black residents. But is the number of voters as great as what was hoped for?

DIAGRAM SHOWING MICHIGAN’S EXIT POLLS; NEW YORK TIMES

Multiple grassroots organizations, including Detroit Action, Michigan Liberation, and Michigan Student Power Network pushed hard in Detroit, and all of Michigan, to help raise voter turnout this election. These organizations worked closely and intentionally with those in the Black and Brown, working class, and student communities within the state. In Detroit specifically, the rise in votes from 48.61% in 2016 to 49.56% in 2020 showed promise in the city’s rise in political investment. However, it is nowhere near the voter turnout in the 2008 (53.15%) and 2012 (50.94%) elections brought to the polls.

The quote attributed to Mark Twain comes to mind with the drop in votes post-Barack Obama’s presidency, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” The 2016 election was wrought with political scandals. Hillary Clinton was accused and investigated for harboring political emails on a personal server, and Trump was, similarly, investigated for the Steele Dossier which held allegations of his conspiring with the Russian government during the race.

The 1970s held a similar tone due to the release of the Pentagon Papers and the Watergate scandal, both of which occurred during Richard Nixon’s presidency. Howard Zinn, in “A People’s History of the United States”, approaches the subject by explaining the state of the country,

There was a deepening of economic insecurity for much of the population, along with environmental deterioration, and a growing culture of violence and family disarray.

Zinn continues, “Clearly, such fundamental problems could not be solved without bold changes in the social and economic structure. But no major party candidates proposed such changes.” Could this be the same issue that kept many Detroit voters from the polls in 2016 and 2020?

A BLACK LIVES MATTER DEMONSTRATION IN DETROIT. PHOTO JOHN BOZICK

In this year alone, American’s have felt deep economic insecurity due to the Coronavirus pandemic, addressed the weight of police brutality in the country, and continued to push for a greater conversation about helping the environment. Yet, as these issues were prevalent, Americans were faced with a president who did little to aid in finding solutions. Though he promised to make America great again and unite the country, there was a lack of Zinn’s aforementioned bold change in our social and economic structure.

During Biden’s first speech as president-elect, he called for unity in much the same way Trump did in 2016. He presents his presidency as a time for America to heal, to come together and create lasting change. Yet, even with this notion, the percentage of voters in Detroit alone is simply not high enough to support the idea that as a city we think Biden can incite the level of unity he has proclaimed.

It may very well be that since the 1970s, voters have been less and less enthused by the politicians that are pitched to us as solutions to America’s problems. Zinn explores this idea, “There was a troubling incongruity in the society. Electoral politics dominated the press and television screens, and the doings of presidents, members of Congress, Supreme Court justices, and other officials were treated as if they constituted the history of the country.

“Yet there was something artificial in all this,” he says, “something pumped up, a straining to persuade a skeptical public that this was all, that they must rest their hopes for the future in Washington politicians, none of whom were inspiring because it seemed that behind the bombast, the rhetoric, the promises, their major concern was their own political power.”

It seems that in the 2020 election Detroit voters were more invested and hopeful than in 2016, but as a city, we still cannot subscribe to Washington politicians in the same way America did before Nixon’s presidency.

A few days after the 2020 election, a Reddit user posted, “I am a housewife from Mississippi. I don’t live in a battleground state. I want to thank all of you who stood in lines for hours or helped campaign for Biden.” She continues, “Thank you for looking out for my children’s future. Thank you for looking out for everyone’s future.” This sentiment is incredibly hopeful for Biden’s presidency, but this may not be what Detroit should be thanked for.

As a diverse city, a city where our majority is made up of the minority, maybe we should instead be thanked for fighting for human rights in ways other than putting our faith in an out of touch political system. After the murder of George Floyd in May of this year, Detroit pushed back hard against police brutality.

Protesters gathered for over 100 days straight, demanding America’s accountability for embedded racism. Detroit helped swing the 2020 election toward Biden, but as a city we recognize this is not all there is to moving our country forward.