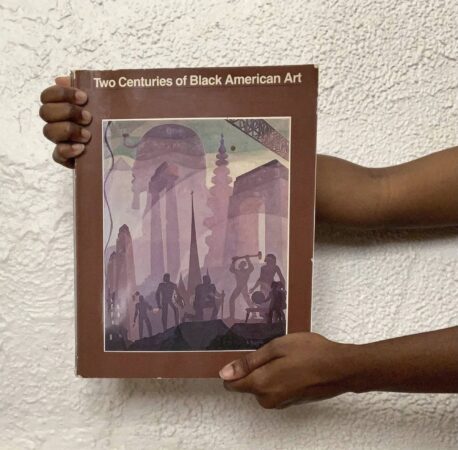

DETROIT-NATIVE ASMAA WALTON FOUNDED THE BLACK ART LIBRARY IN FEBRUARY 2020

Growing up with family in the field, Detroit-native Asmaa Walton was always surrounded by art, spending time in the DIA while her mother worked. Yet, despite the ever-presence of material brought home pertaining to galleries, art exhibitions, and other artistic mediums, it was not until some years into her college career that Walton would come up with the idea for the Black Art Library Project, initially after she began to realize how the field of art education was failing black communities.

Dabbling briefly in the arts, Walton initially yearned to become a chef and enrolled in a Chicago-based culinary school before eventually returning home to attend Michigan State University [MSU]. Like many, she entered MSU not quite set on an idea of what she wanted to go into, first going through classes in athletic training, she later switched to taking basic art classes, which, eventually led to her discovering art education.

Graduating from MSU and not wanting to enter the education field just yet, she enrolled in an arts politics program through New York University [NYU], after which led her to an internship at the Toledo Museum of Art, followed by time at the Saint Louis Art Museum.

It was during her time at both museums that the idea for the Black Arts Library Project began to form.

THE IDEA FOR THE BLACK ART LIBRARY

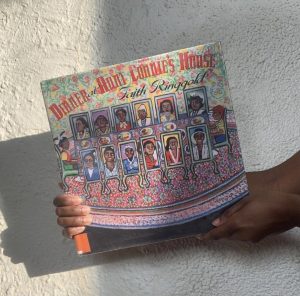

DINNER AT AUNT CONNIE’S HOUSE. PHOTO BLACK ARTS LIBRARY

“During my time working at these museums, I saw how certain audiences don’t become a part of their regular visitors. A lot of black and brown like citizens that live in these cities don’t come to the institutions and both of the ones that I worked at were free museums,” Shared Walton while discussing what initially led to her coming up with the idea for the Black Arts Library Project. “So a lot of times people that have lived blocks away from these institutions for years, have no idea that it’s free and they can just come in.”

“In the museum, there were, at a certain amount of time, only about like six works out by African American artists and I thought that was kind of weird. I posed a question about it to the person who was over me in my fellowship and they were like “hey, that’s a good point, let me ask someone about it” and they sent out an email to the curators,” Walton added.

After sharing how a curator approached her saying next time, before asking questions, she should talk to them first, Walton stated, “that kind of started to open my eyes to a lot of the internal things that were going on in museums, which made me realize that this was probably going on at a lot of different kinds of arts institutions.”

Sharing that she was always the art connoisseur in regard to visual art amongst her friends, Walton came up with the idea to begin showcasing work from black visual artists on her personal social media pages. This, in turn, eventually led to the project becoming massive in scope, ultimately becoming the Black Art Library.

I was thinking that I just wanted to create some kind of resource, I had no idea how it would be used, I really had no real plan for it but I was just going to start building it,” stated Walton, “I’m just gonna start collecting these books and we’ll kind of see what happens.

Announcing the Black Art Library project shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic hit in March, the quarantine offered Walton the opportunity to stay inside, cataloging and collecting work to be featured through the project.

POPUPS AND EXHIBITIONS AMID THE PANDEMIC

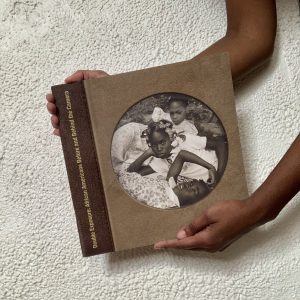

DOUBLE EXPOSURE AFRICAN AMERICANS BEFORE AND BEHIND THE CAMERA. PHOTO BLACK ARTS LIBRARY

Acquiring material initially all herself from searching used bookstores and online Walton began to receive donated books around April and the Black Art Library began to grow further. Moving back to Detroit in July, Walton eventually met artist Tony Rave, who presented her with the opportunity to showcase a small popup exhibition at a space in Highland Park, which served as a gathering space for black artists.

Hosting her small outdoor exhibition amid the pandemic, a chance encounter on the last day of the showing led to the Black Library Project landing where it’s headed today, with an exhibition showcase at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit [MOCAD]. Connecting with MOCAD’s Jova Lynne, an opening was found in the exhibition schedule from January 21 to April 18, 2021.

Of her goal for the Black Art Library project, it all goes back to art and education for Walton.

“The only hope that I have is that maybe they’ll come and they’ll learn one new thing. That’s literally the only thing that I’m hoping for. Maybe they’ll see one name that piques their curiosity, they’ll learn one small piece of art history that they had never heard anything about,” Shared Walton when discussing what she hopes people get out of the Black Library Project. “Just if they can leave with like one small thing that they didn’t have knowledge wise when they came, but I do want people to have somewhat of an appreciation for the things that they see even if it’s not something that is you know what they’re interested in.”

Showcasing the Black Art Library in Detroit also allows Walton to tell a story that many people haven’t heard in the past, one of all the unique works created by black visual artists. MOCAD, which recently showcased the New Red Order: Crimes Against Reality exhibition that presented a conversation around settler colonialism, is showing that as an institution, they’re willing to showcase art from a perspective not talked about in years past.

But as far as the conversation goes, Walton shares that it’s incredibly important to showcase the work done by black visual artists.

I think it’s super important, especially because of where MOCAD is based. Detroit is an 80 percent black city and that is the highest population out of any city in the United States,” stated Walton. “So I think they definitely should have a certain dedication to telling certain stories and make sure that people in the community feel like their voices are heard and really just being cognizant of everything that’s always going on like literally right outside the walls because MOCAD also is positioned right in the middle of the city and there’s literally so much that still goes on, right outside those doors. And, the same goes for the DIA, because they’re literally right down the street from each other.

“I think a lot of times just, historically, those weren’t places that made people of color feel comfortable and that’s continued kind of silently over the years,” she added. “But, I think now we’re getting to a point where museums and other institutions, they’re not really able to let things go on without people seeing anything anymore. A lot of the places are aware that they have to have to make some changes and I think MOCAD definitely understands the importance of being able to tell stories and to make sure that they’re perceived as a space that’s welcoming to the surrounding community.”

With the exhibition opening in a few weeks, be sure to check out the Black Art Library from Walton on Instagram at @blackartlibrary, or stop by MOCAD to see the exhibition in person. Additionally, donations to the Black Art Library are also an option and if you would like to contribute work to the project, Walton may be reached at asmaawalton@gmail.com.

Subscribe to our newsletter for further updates on all things Detroit and more.