It was July 24th, 1701 that Detroit was announced Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit, shortened later to the name we know well, by Frenchman Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac. Over the past 320 years, however, Detroit has changed greatly in both what the city provided and how the city looks.

Before Detroit was founded, the area was inhabited by native people of the Wyandot, Potawatomi, and Odawa as well as the western nations of the Iroquois League. The Iroquois League was in broad control of the land prior to the peace treaty in 1701 with the French and utilized the land for the fur trade.

Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit, as a part of New France, began growing due to its lucrative inland as well as the Great Lakes which connected easy access to transport furs. Soon free land was offered to colonists as a way to attract families to the Detroit region. The growth of the region was slow but steady.

In 1760, however, Fort Detroit was surrendered to the British after France’s loss of the Seven Years’ War. This led to a fall in population, which inevitably rose again after Great Britain ceded Detroit to the freshly established United States in the 1783 Treaty of Paris. Detroit, however, stayed mostly under British control for another decade.

It wasn’t until 1796 after the Jay Treaty that Britain stopped controlling trade, relations with their native allies, and using the area to keep weapons and supplies used to raid the American settlers. During this time General Anthony Wayne negotiated a treaty with native peoples in which the tribes ceded the Fort Detroit area to the United States.

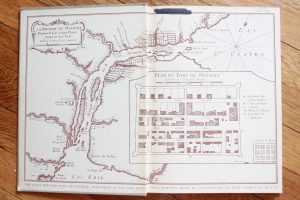

PHOTO OF PLAN DU FORT DU DETROIT. THIS IS DETROIT

The 19th century for Detroit brought change both in terms of industry and aesthetic. Fort Detroit’s simple layout was destroyed in 1805 by a massive fire, after which the city was redesigned and rebuilt. The street plan, devised by Augustus B. Woodward was made to look similar to Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s Washington D.C. design.

The circular street plan was designed in an effort to create radial traffic patterns in which Campus Martius Park would be in the center. This in turn was hoped to enable parks and boulevards to be filled with greenery and cared for with ease—something Detroit still utilizes to its advantage today.

Detroit was booming and easing into its own rhythm, unknowingly readying itself for the automotive revolution that was only a few decades away. The city expanded, utilizing the river and the newly established rail line that ran parallel to the water as efficient ways to transport goods. It was during this time that Detroit became known as the Paris of the West.

Beautiful architecture was brought to life throughout the city, much of which can still be seen and inhabited in neighborhoods such as Boston Edison and Indian Village. Washington Boulevard, accompanied by newly implemented electricity, was also a great contributor to this nickname.

As the 20th century graced the ever-growing city of Detroit, the automotive industry and the Great Migration thrust Detroit into the future, changing it forever. Now as we look back to the city’s history in honor of its 320th birthday, there is something to be said of what has come to be Detroit’s synonym: resilience. From the day Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit was established to the fire that forced the city to start again, to the Great Migration, to the 1967 Riots, to bankruptcy, to the COVID-19 pandemic, to today, Detroit still stands. We still stand.

So happy birthday Detroit, happy birthday Detroiters, may we continue to stand, together.

For more information on the Tribes native to this area, check out the National Park Service’s information, this Model D article, or check out The North American Indian Association’s webpage.

For more information about the Great Migration check out our piece on it, or grab the book “Black Detroit” by Herb Boyd for additional information on Detroit’s Black population.

As always, be sure to subscribe to our newsletter for regular updates on all things Detroit and more.