Public transit throughout the world has suffered through the Covid-19 pandemic, but maybe not in the way one would think. Prior to the pandemic, roughly 100,000 Detroiters and those in the Metro area utilized bus transportation daily. This resulted in stark fears of the transmission of the virus in March, 2020 and service was halted.

The safety of both riders and drivers became the utmost priority to both SMART and DDOT transit services. The reinstatement of service that same month brought many new precautions. These have proved to be greatly effective, yet, as the days grow colder, the ripple effects of these precautions are causing unsettling problems.

Many studies have been done across the globe to identify the risks of public transit. According to a local study by Transportation Riders United (TRU), public transit has proven to be low-risk. In TRU’s report, places with extensive contact tracing, such as Tokyo, Austria, and Paris, were cited. These places found no ties of infection to public transit, after enacting safety precautions.

Both SMART and DDOT’s precautions have been essentially the same since their service was reinstated. Masks are required and offered to patrons if they are without. Hand sanitizer is encouraged and provided. Deep cleaning of the busses is done during routes and upon return to terminals. Fares are waived and all individuals use the busses’ rear doors for entry and exit, aside from handicap use, to diminish interactions between the drivers and riders.

SMART FIXED ROUTE RIDERSHIP DURING COVID

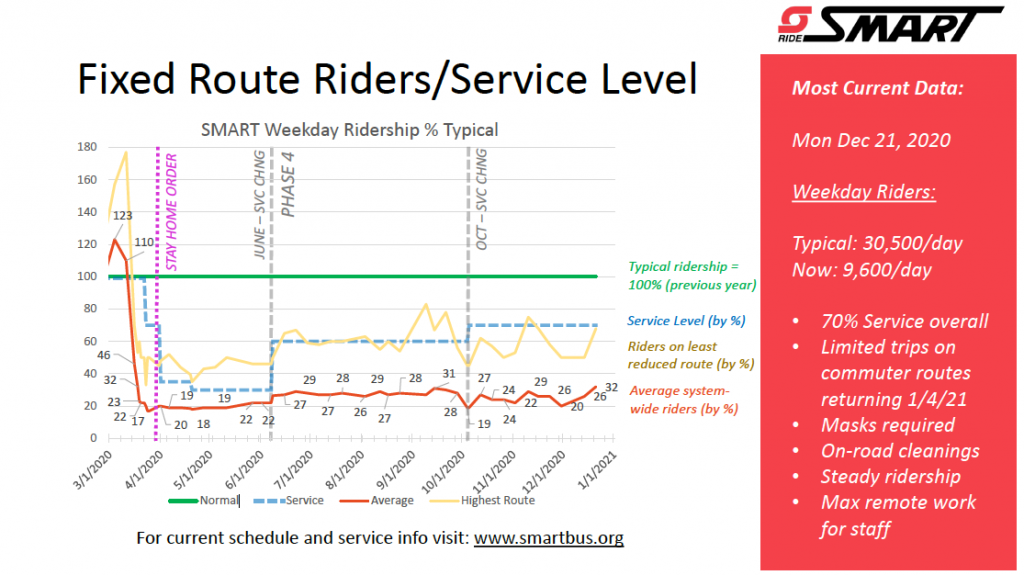

Even with proof of its safety from Detroit and other cities around the world, public transit’s ridership numbers have fallen greatly. According to the Deputy General Manager at SMART, Robert Cramer, ridership during the last two weeks of March fell from 123% to 17%. The fall was swift and came only a few days before the first Stay-at-Home orders. SMART has yet to see ridership above 32%.

The assumptive reasoning of lessened ridership is in part thought to be fear of safety, even though individuals like Cramer have worked hard to be informative about public transit’s low-risk. “We’ve been really careful and deliberate along the way of communicating proactively,” he says. Individuals working from home, or those out of work due to the pandemic, are also assumed to be a substantial factor of this low percentage.

Financially, this low percentage hasn’t been detrimental for either SMART or DDOT’s services. Prior to the pandemic, both services depended on fares to make up roughly 11-12% of their budgets. Both transit services were compensated for the lack of this money through the Cares Act.

The remaining money that DDOT received was put towards the transit system’s safety precautions. This included the installment of safety barriers to protect the bus drivers from what has come to be the system’s largest adverse effect of their precautions.

DDOT BUS DRIVER BEHIND SAFETY BARRIER

In order to achieve social distancing on their buses, DDOT enacted a rule of allowing only 10 passengers on at a time. When ridership was at its lowest, this may not have been that great of an issue, but as more people return to work, and winter sets in, this precaution is becoming a severe headache for bus drivers.

Due to the lack of fares, DDOT has seen more joyriders utilizing the busses as an activity to break up their day, or as a place to get warm. Normally this wouldn’t cause an issue, but with limited space, a few joyriders can result in the inability of transportation for those utilizing the service to get to work.

This is detrimental for those in need of transportation and creates conflict between drivers and passengers when individuals have to be left at the bus stop. In the mind of DDOT’s Director of Transit, C. Mikel Oglesby, the idea of leaving passengers in need behind is currently necessary, but also counterintuitive and frustrating. “I’ve been in public transportation 30 years,” he

DRIVER AND BUS, PHOTO SMART

says. “I am trained to put as many people on a bus as possible. To get them out of their cars, reduce traffic, and have them be comfortable and get to where they need to go.”

Oglesby continues, “Covid-19 is forcing, not only myself but everybody in public transportation to do the opposite of what they have been trained to do. Reduce the amount of people that can get on, pull out and leave the ones that need transportation. It’s insane. The problem is, there’s no easy fix.”

Until more passengers can be allowed safely onto the busses, there’s not much transit services can do. Many drivers don’t want to put themselves in harms way, communicably or physically, which results in many of them not driving on a daily basis. The DDOT system currently only has 260-270 drivers per day. In order to run and provide full service, however, 477 operators are needed.

This seems to be an unsolvable issue for transit services, although small aids to the problems are being put into place.

DDOT C. MIKEL OGLESBY VACCINATION

Oglesby has enacted de-escalation training for drivers in hopes this helps keep unsettling interactions to a minimum. There is also talk of accepting fares again, which may lessen the number of joyriders on the buses. These things, along with the safety barriers, will hopefully resolve the issue enough to continue service.

Hope may just be on the horizon as DDOT transit workers have begun receiving Covid-19 vaccinations. Oglesby was among the first to receive his initial shot on January 8th.